Background¶

Synopsis¶

Computational tools have been developed to test for patterns of shared divergence times across taxa predicted by community-scale, environmental processes that drive speciation across communities of species [1][2][4][5]. These include tools designed for genetic data collected using Sanger sequencing technology. Such datasets usually have one to a relatively small number of loci, where each locus comprises approximately 500 linked base pairs or so. The tools developed for these datasets use approximate Bayesian computation (ABC) [1][2][4], and have been shown to be biased and sensitive to prior assumptions [3][7]. ecoevolity is a full-likelihood Bayesian approach designed for much larger, genomic datasets, comprised of of unlinked characters from across the genome, and has been shown to be more robust than ABC approaches [5].

So, if you have a Sanger dataset (a small number of loci of linked bases), are you better to:

Use a full-likelihood approach despite the data violating the assumption of unlinked characters?

ABC methods that accomodate loci of linked characters but can suffer from bias and prior sensitivity?

In this project, we will use simulations to try to determine which approach is better.

Introduction¶

The background information below will assume some knowledge of the types of comparative phylogeographic models implemented in ecoevolity. The ecoevolity documentation provides a brief and gentle introduction to such models here. For more details, please refer to [5][8][6].

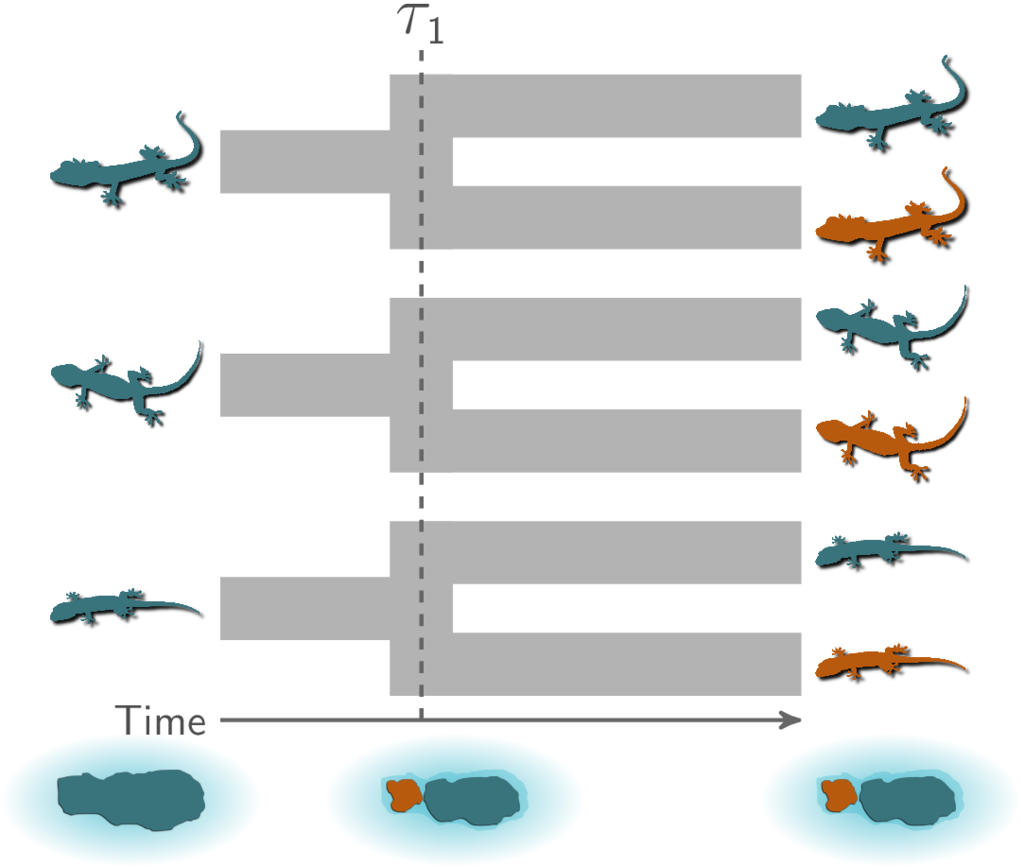

Community-scale, environmental processes that drive speciation across communities of species will cause divergence times across taxa that are temporally clustered (i.e., divergences that occur at the same time across species). For example, let’s assume we are studying three species (or three pairs of sister species) of lizards that are co-distributed across two islands, and we want to test the hypothesis that these three pairs of populations (or species) diverged when these islands were fragmented by rising sea levels 130,000 years ago. This hypothesis predicts that all three pairs of populations diverged at the same time:

All three pairs of lizard species co-diverged when the island was fragmented.¶

If we want to evaluate the probability of such a model of co-divergence, we also need to consider other possible explanations (i.e., models). For example, perhaps all of these populations were founded by over-water dispersal events, in which case there is no obvious prediction that these events would be temporally clustered. Rather we might expect the dispersal events to have occurred at different times for each species. Or maybe two pairs of populations co-diverged due to sea-level rise, but the third at a different time via dispersal.

So, there could have been 1, 2, or 3 divergence events in the history of our lizard populations. If there was 1, all three pairs of populations diverged at the same time. If there were 3, they all diverged at unique (independent) times. If there were 2, two diverged at the same time and other diverged independently. For this last scenario, the pair of populations that diverged independently could have been any of our three pairs. So with three pairs, there are a total of 5 possible models explaining their history of divergence times.

The methods we will be using in this project take a Bayesian approach to comparing these 5 models, and approximate the posterior probability of each of them.